The Other Side of the Rainbow: Young, Gay and Homeless in Metro Atlanta

[“The Other Side of the Rainbow: Young, Gay and Homeless in Metro Atlanta” is part 1 of a 3 part series on LGBT issues. Bookmark this page for updates.]

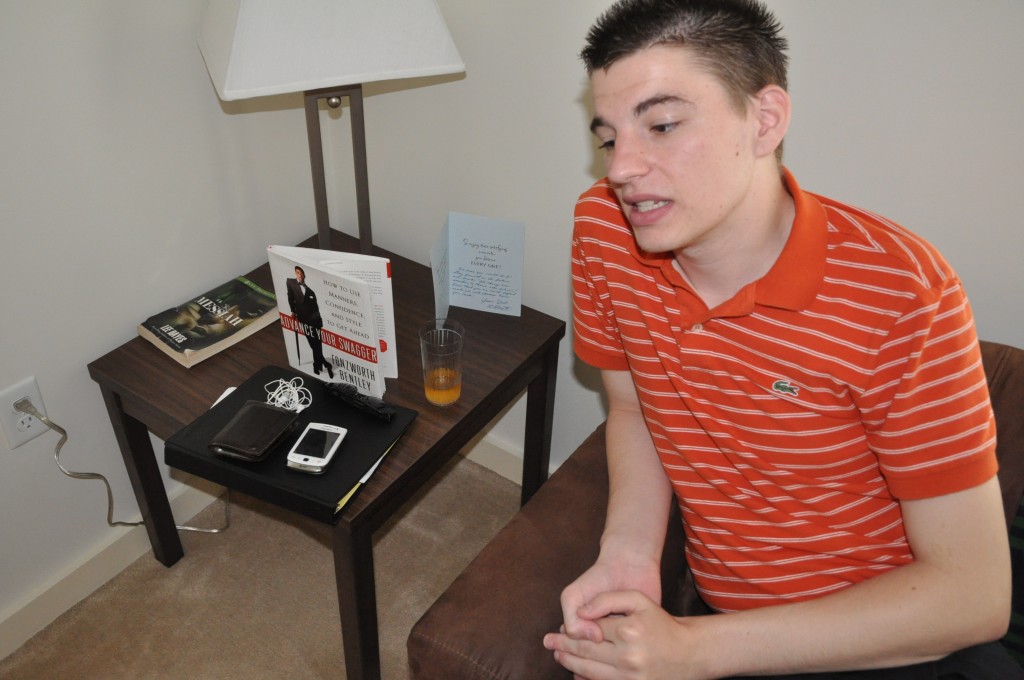

In April 2008, Brian Dixon was 18-years-old and homeless. Being gay, he says, only exacerbated his predicament.

After allegedly enduring years of mental and physical abuse, at age 14 Dixon left home to live with his grandparents. Within a year, they placed him in Georgia’s foster care system. From there he bounced around to several group homes. He’d quit high school, but earned a GED before officially “aging out” of the foster care system.

Dixon, who grew up mostly in Fort Benning about 90 miles southwest of Atlanta, had dropped to his knees many nights, fervently praying to be granted an extension to remain in the foster care system a bit longer while he worked on his nursing degree from Georgia Perimeter College. His new caseworker, whom Dixon describes as a “devout Christian,” was not in support. She’d convinced her superiors that he was not “a good a candidate” for that privilege. He thinks it’s because he’s gay. Within two weeks, Dixon was dropped off with his few belongings at a Southwest Atlanta homeless shelter.

“I was scared; I had nowhere else to go,” recalls Dixon. “That first night they sent me to Covenant House and I just could not handle it. I was still in the foster care mindset. It didn’t really register in my mind that I was actually homeless.”

Strict rules and a curfew at the facility for those aged 17-21, didn’t mesh well with Dixon’s school and work schedule. He tried traditional adult shelters briefly, but ultimately ended up living on the streets of Atlanta. That catapulted him onto a yearlong emotional and heart-wrenching odyssey of illegal drug use, prostitution and “couch-surfing” from one friend’s house to another. He claims in the summer of 2009, he even fell victim to a brutal roadside rape at the hands of two strangers.

Atlanta-based licensed counselor Tana Hall says Dixon’s experiences are common among displaced gay youth.

“A lot of young people in this predicament get sexually exploited because of their homeless situation,” says Hall, who counsels Lesbian Gay Bisexual and Transgender (LGBT) youth at Atlanta-based non-profit, YouthPride. “A lot of young gay boys find themselves trading sex for basic necessities like food and shelter but they won’t tell you that. They’ll tell us, ‘I’m staying with this 45-year-old guy.’ They’re happy to have groceries and a place to stay, but they’re not admitting what’s really going on there.”

As Hall suggests, Dixon is among legions of LGBT teenagers and young adults kicked out of their homes and out of foster care homes primarily because of their sexual orientation. Many claim that the discrimination they face – often rooted in religious conviction – even extends to homeless shelters and into the foster care system. The ostracism, Dixon says, is magnified 10-fold for transgender youth whose androgynous appearance is often harder for others to embrace. Halls says she’s heard staffers at local Christian-based shelters make homophobic comments and it’s upsetting. She often tries to avoid sending her clientele there because she fears discrimination, but sometimes it’s the only option available.

“There’s a disproportionate number of homeless LGBTQ young people out there because of a lack of acceptance from their families and others around them,” says Hall, who also answers calls on YouthPride’s crisis hotline. She and other advocates however, often add an “I” and “Q” to the common acronym, in reference to “intersex,” persons born with both male and female genitalia and “questioning,” as in those questioning their sexual orientation.

“The majority of calls I get on our helpline are young people who have run away because they did not feel that they were accepted in their home,” Hall says. “The primary reason that these young people are homeless is not because of issues like substance abuse or mental illness; it’s due to a lack of acceptance about who they are [from others]. It’s a societal issue.”

Dixon claims the only facility he’s ever formally been kicked out of was one touted as a “Christian group home.” Upon arrival, he says, he was required to sign a form agreeing to never disclose his sexual orientation. He tried unsuccessfully to conceal his sexual identity there.

“People kept asking me about it and I wouldn’t answer them; once they found out I was gay, it was pretty much downhill from there,” recalls Dixon.

– continue reading –>

Newsfeed Archives

- November 2024

- October 2022

- June 2022

- May 2022

- February 2022

- January 2022

- December 2021

- November 2021

- August 2021

- July 2021

- May 2021

- April 2021

- February 2021

- January 2021

- December 2020

- October 2020

- August 2019

- August 2018

- May 2016

- September 2014

- April 2014

- December 2013

- April 2013

- August 2011

- July 2011

elsewhere

- An interview with Karlan Sick, Board President

- BOOKS CAN HELP INCARCERATED TEENS SUCCEED

- Books Through Bars

- Distribution to Underserved Communities Library Program

- Juvenile Justice Information Exchange

- Life Lessons Through Literacy for Incarcerated Teens

- Passages Academy Libraries

- Passages Academy Schools

- Read This

- What's Good in the Library?

- Women and Prison